#5 in a series on Learning in Different Contexts

Guest post by Michael Stout (@mickstout )

Michael is a Canadian, born in Toronto, who has lived in Japan since 1997. He has taught learners from 3 to 80 in language schools, secondary schools and universities. He has an M.Ed (TESOL) from Temple University. At present he teaches at Toyo Gakuen University and Shibaura Institute of Technology. He was the founding chair of the Nakasendo English Conference. He has have been involved in the Japan Association of Language Teaching for over 10 years, and has participated in teacher training projects in Laos, the Philippines, and Bangladesh through Teachers Helping Teachers.

I seldom see a doorknob. Where I live doors open automatically. The toilet in my apartment resembles a jet fighter cockpit. It’ll power wash and dry my bottom with just the touch of a couple of buttons. Toilets in Japan are very high tech, highest in the world, I’ll bet – and that’s not all! Mobile phones have smart cards in them and you can use them to pay for a ride on the train, and you can buy a coffee from a vending machine by just touching the phone to a sensor on the machine. Every one of my students has a mobile phone, and they are the norm for university students in Japan. Young people in Japan spend nearly 2 hours a day doing e-mail, and browsing the web on their mobile phones. No surprise right? Technorati’s State of the Blogosphere for 1 May 2006 reports that 31% of all the blog posts in the world are written in Japanese, followed by English at 25%. Now that’s a surprise!

So, you’d expect all this technology to be in Japanese classrooms too, wouldn’t you? Well, it’s not.

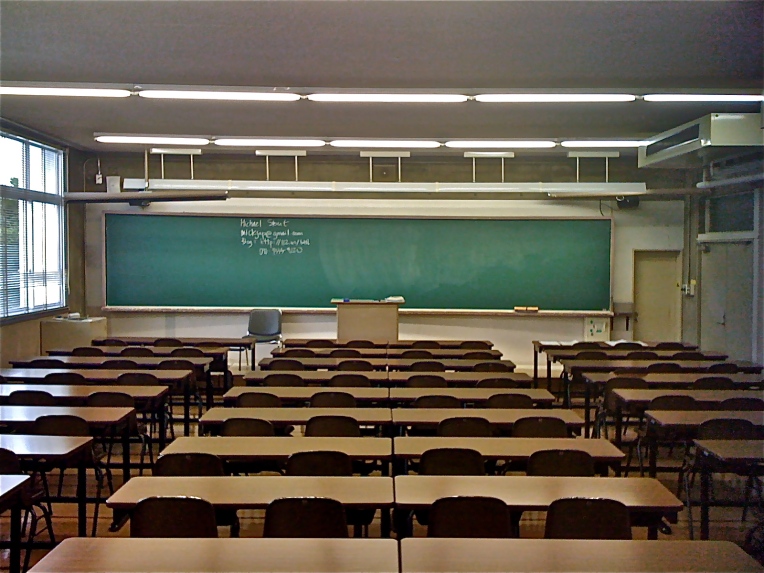

I’m choking on chalk dust every day. Most classrooms I teach in still have blackboards. Interactive whiteboards are becoming ubiquitous in classrooms in the UK and elsewhere, but not here. There just isn’t much of a connection made between education and technology in Japan. When I was teaching at a high school, I can only remember ONE classroom, apart from the computer room, that was connected to the internet. When I refuse to accept handwritten assignments, rather requiring my students to submit their assignments as attachments by e-mail, they are shocked. I’ve had students, even at the Institute of Technology where I teach, complain about my insistence that they do assignments on a computer – none of their other teachers do, after all. Suffice to say that, despite appearances, few learners and teachers are ‘digital natives’ in Japan. Nevertheless, I’ve been integrating technology into my teaching for the last 4 ½ years.

I’m choking on chalk dust every day. Most classrooms I teach in still have blackboards. Interactive whiteboards are becoming ubiquitous in classrooms in the UK and elsewhere, but not here. There just isn’t much of a connection made between education and technology in Japan. When I was teaching at a high school, I can only remember ONE classroom, apart from the computer room, that was connected to the internet. When I refuse to accept handwritten assignments, rather requiring my students to submit their assignments as attachments by e-mail, they are shocked. I’ve had students, even at the Institute of Technology where I teach, complain about my insistence that they do assignments on a computer – none of their other teachers do, after all. Suffice to say that, despite appearances, few learners and teachers are ‘digital natives’ in Japan. Nevertheless, I’ve been integrating technology into my teaching for the last 4 ½ years.

In January 2004 I started a teacher blog in order to participate in a blogging project that my students were doing in another class. I’ve written extensively about it in a paper I wrote with Adam Murray called Blogging to learn English: a report on two blog projects. All I will say here is that I was disappointed the students didn’t blog more. Interestingly, two of them started blogs in Japanese, and kept them up longer than their English blogs. Another interesting thing about this group of kids is that now many of them post on facebook almost daily, and their exchanges with each other and other Japanese are usually in English. So they are willing to do it on their own, but not so keen to do it when a teacher asks them to do it.

It’s complicated. I haven’t given up hope. I’m still using web 2.0 applications. Whenever I think I should just pack it in and forget all the hassle of using a CALL room and web 2.0 applications in my courses I remind myself that most of the time my students feel that they can’t use English, except in my class (or in another class with a native English speaking teacher, if they have one).

One needs to understand that this digital natives vs. digital immigrants dichotomy is just plain wrong, especially in Japan and other countries in Asia. It’s not just about the national culture or even the generational culture. It’s about the specific educational culture. The trouble is that most of the research is done in European cultures (including Australia, New Zealand, North and South America.). This research assumes a fairly homogeneous educational culture. The assumption is that the difference in other countries is affluence and modernity. That assumption is wrong. Japan is affluent and modern, but its educational culture is not European, and that makes all the difference.

We need more action research. We need to see what’s going on in a variety of learning contexts. We need to see what’s happening in classrooms.

For further reading please see:

Birchley, Sarah Louisa and Taylor, Clair (2008). Virtual cards:an action research project exploring how far online flashcards can invigorate vocabulary learning for students. The Bulletin of Toyo Gakuen University 16, 47-55. Retrieved 3 October 2010 from http://opac.ndl.go.jp/articleid/9437441/jpn

Stout, Michael (2009). Web 2.0 and Mixed Ability EFL Classes in Japan : Challenges and Possibilities. The Bulletin of Toyo Gakuen University. 18, 247-257. Retrieved 3 October 2010 from: http://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/110007043508/

Taylor, Clair (2009). Setting up a MALL?CALL tracked self-study component to a course. The Bulletin of Toyo Gakuen University. 17, 233-242. Retrieved 3 October 2010 from http://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/110007043508/

The lack of educational ICT in Japan really surprises me. I had assumed that the land of miniaturisation and connectivity would have naturally extended this into the edu sphere. Enlightening and assumption challenging, thank you.

LikeLike

Thanks for the view from inside Japan and the important point is that educational innovation must happen within the specific education culture. I’ve found it helpful to break down “culture” into a specific history of a specific place.

In that context, I think it’s important to see that “European” vs “Asian” is a little broad . The differences between Latin America and Northern Europe is significantly different. Even within America with 300+ million plus people, many urban centers, and diverse economic regions, it’s important to “drill down” to the right focal points to get an understanding of what’s “going on.”

The opportunity is that once we focus on the diversity of truly historically specific and place based education there are huge numbers of positive deviance that might replicate with an much smaller effort than is presently believed.

LikeLike

My response was a bit too long to leave here! Please visit : http://rimach.wordpress.com/2010/10/09/260/

LikeLike

Hello Phil, Michael and Mari,

Thank you for your comments.

Phil, I think you got it nailed – minaturisation and connectivity ie: mobile phones. Read Mari’s response to thsi article on her blog. The link is above. I can totally believe that a Japanese student would want to compose 2000 word essays on a mobile phone rather than use a computer keyboard. One of my facebook friends, Matt Apple (@manzano0627), has just shared an interesting piece by the BBC that is relevant to this discussion: Japan has fewest digital friends. Matthew asks this question: ”A culture that embraces fewer but closer friendships”? Or “a culture in which high schoolers and university students still don’t have computers, despite the fact the hardware and software is made here”? He received this response:

“I think the clear preference for most young people in Japan is the keitai (ie:moble phone)… NTT Docomos’s policy has been to charge excessively and ‘encourage’ the use of the least taxing (for them) online system, texting. Its been that way since the web took hold here over the past 15 years or so… Also, the family PC is not used in their own room, privately, so getting comfortable with being online is tough here… As a cultural point, people tend to usually have very few friends, even college students… So both are true…”

I think these observations support Michael’s comment above, and I shouldn’t have suggested that European (0r any other) culture was homogeneous. The point I was trying to make was that most of the research in our field is being done in “inner circle” educational contexts, and the conclusions drawn from the research are seen to be generalisable, when they aren’t always.

Thanks again for the comments.

Cheers!

LikeLike

A former colleague of mine at Doshisha University wrote a short report about the need for computer literacy among students at his university. The paper is dated from 2005, but I have found the same problems among students five years later (I teach part time at Dodai). Keeping in mind that Doshisha is one of the top private universities in the Osaka-Kyoto-Kobe area, with many students (close to half) coming from relatively well-to-do families, the number of students who are incapable of handling a web browser and reading/writing simple email even in their native language is astounding. I’ve been fortunate the past couple of years to teach tech college students (my full time gig) but even then plenty of students have never seen a computer until they step foot on campus at the age of 15-16. And these are tech students, mind you. They will be using computers on a daily basis at work once they graduate. It’s not just about money for internet access and the PC itself (btw, internet speed here is FAST and CHEAP compared to the US and the UK). It’s about the educational system, pure and simple. I had to type my papers in high school and university (80s and early 90s), and my siblings had to send papers by email and register for courses online (mid to late 90s). Japan is nowhere near that degree of computer literacy.

LikeLike

To takingleaveinjapan

There might be another way to look at it. What I see is that the computer terminal is starting to fade away as the internet device of choice for many all over the world. Not really surprising that it first emerges in Japan given their head start on all things digital.

I had a recent conversation with a 16 year old about the iPad. His reaction is that it’s just a big iPod for grownups. He would much rather have the iPod because he can put it into his pocket. I was amazed. But after a little thought perfectly natural.

In the States I’ve seen plenty of examples of kids using their phones they way my generation uses computers. I don’t own a smartphone. My lifestyle ( comfortably retired ) does see the mobility as an advantage. my laptop is just fine. But, there is little doubt that if I still had either a day job or traveled alot I would pretty quickly use either a smartphone or an iPod like device to stay connected.

The issue of education is separable. Without having been in that context, I don’t have much to add. But I do follow both tech and education very closely. @Snewco is a school that has taken advantage of a recently launched Verizon program to use smartphones instead of and in addition to “computers” Based on what I see at Twitter, my strong hunch is that it’s gong to be a major factor in education going forward.

LikeLike

The disconnect between culture in and out of the classroom is incredible. It is happening all over the world, and only pockets seem to have figured out that the classroom should reflect the larger community. Great post!

LikeLike